When discussing the relationship between DNA mutations and cancer, it is mandatory to differentiate between germline mutations and somatic mutations. The former are hereditary mutations that have been associated with the risk of cancer development; they occur in germ cells (cells that will give rise to sperm or eggs) and are passed onto every cell of the offspring. BRCA 1 and 2 mutations stand as examples of germline mutations associated with breast cancer susceptibility. In contrast, somatic mutations are acquired, nonheritable, changes in DNA sequence in cells other than germ cells. They occur after conception, cannot be passed onto offspring, and develop in specific tissues (e.g. breast or lung). Only a limited percentage of cancers have a clear hereditary component, and even in those cases in which cancer susceptibility is clearly inherited, acquired mutations are needed for cancer to develop.

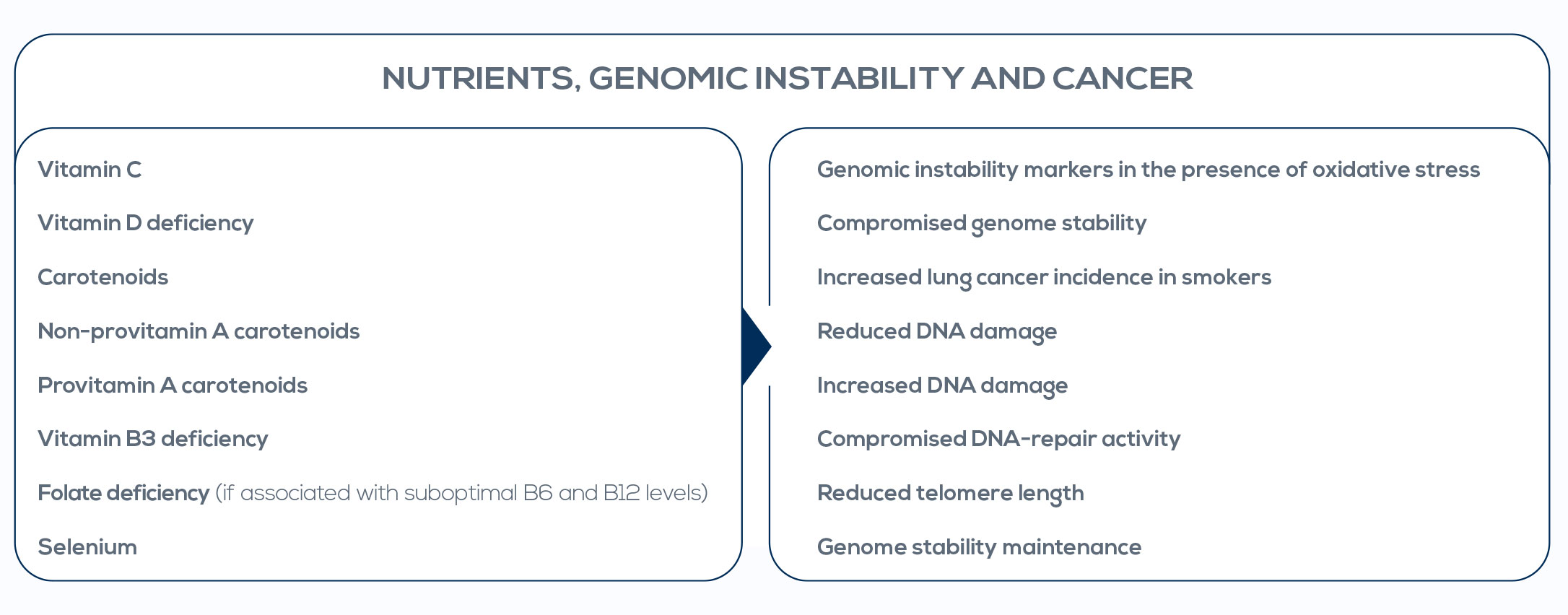

In particular, the progressive accumulation of somatic mutations can lead to cancer and is indicative of genomic instability. Contrary to germline mutations, genomic instability is not a marker of the risk of cancer; rather, it is indicative of the cancer prodromal stage. Researchers already gave proof of concept that genomic instability analysis is useful to assess the cancer prodromal stage. And, fortunately, genomic instability is preventable and actionable. Nutrigenetics and nutrigenomics are interesting tools to avoid genomic instability through a simple approach based on lifestyle. Genome integrity has been shown to be highly sensitive to nutrient status, with optimal nutrient levels differing among individuals.